If you had to guess, would you say that all languages of the world are equally complex?

Most people reply to this question with a definite “no”. Perhaps they do so without the best of arguments, such as when they think that somewhere in the world, there are primitive languages at the level of “Me Tarzan, you Jane” (there aren’t). Or perhaps because they think that some languages are easier to learn than others, based on how similar they are to their native tongue (also not an objective assessment). Nonetheless, they would be right. And contrary to that, most linguists would say that the answer is “yes”. And they would be wrong!

For decades now, the consensus among linguists has indeed been that all languages are equally complex. That is, that what is less complex in one language (for example, its sound system), is bound to “catch up” for complexity in another area (such as syntax or morphology). For example, a language with only 10 sounds may have a very complex way of forming words. Thus, all languages maintain roughly the same amount of complexity. This idea stems mainly from what was initially a supposition, and never stated as a fact:

[…] impressionistically it would seem that the total grammatical complexity of any language, counting both morphology and syntax, is about the same as that of any other. This is not surprising, since all languages have about equally complex jobs to do, and what is not done morphologically has to be done syntactically. Fox, with a more complex morphology than English, thus ought to have a somewhat simpler syntax; and this is the case.1

You can find the quote above in many general Linguistics manuals, taken as a given. Even opposed schools of thought (such as those who believe language is mainly innate, and those who believe that it is mainly acquired) have one thing in common: none of them disputes that the overall amount of complexity is about equal in all languages.

Even when complexity within language systems is finally questioned, take any random introductory course on Linguistics, and you are likely to read something like:

“People think the same thoughts, no matter what kind of grammatical system they use”.2

That is, even if we admit that some languages are simpler than others, please don’t go imagining that some people are more “simple-minded” than others, or that their language limits in any way what they think about! This is quite welcome in the age of “diversity” and political correctness. But, step by step, I hope to show that whether we look at the problem from the point of view of language structure, OR thought, it is not quite so simple.

Language structure

The problem with assuming that the language structure is equally complex is that even a layman can easily discover that this is not true. Take German, for example: Its grammar is known to be more complex than English grammar, with cases, declensions, etc. But nowhere else in the language do you find something simpler than English. No “catching up” takes place. If the theory was true, German morphology (word formation) would be simpler than in English, for example, but that is not the case. Nor is the German sound system any simpler.

The opposite is also true with other languages, like the famous case of Indonesian (and most particularly Riau Indonesian), which is known to be simpler in pretty much every respect. It has a reduced number of sounds, a very simple grammar, very simple morphology, etc.

Language and thought

What about the idea that, regardless of grammar, people still think the same thoughts, as stated in the quote above? Once again, even if you have never studied any foreign language, you can see that that is not the case. A tribe in the middle of Papua New Guinea has no reason to be thinking about the complexities involved in building a skyscraper. They have no immediate use for it. And a New Yorker hardly ever thinks about how to hunt in the middle of the forest, because it is not within his or her immediate experiences. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t capable of doing so, as we shall see later, but it does mean that some people really think simpler thoughts than others, or at the very least, have very different habitual thoughts and ways of reasoning. And some habits can become so ingrained as to cancel others almost definitely. “If you don’t use it, you lose it”, as the saying goes. This does not have to be attached to any moral judgment or discrimination, unlike what many “experts” trying to shut down this debate would pretend.

Prejudice and discrimination in the Imperial past

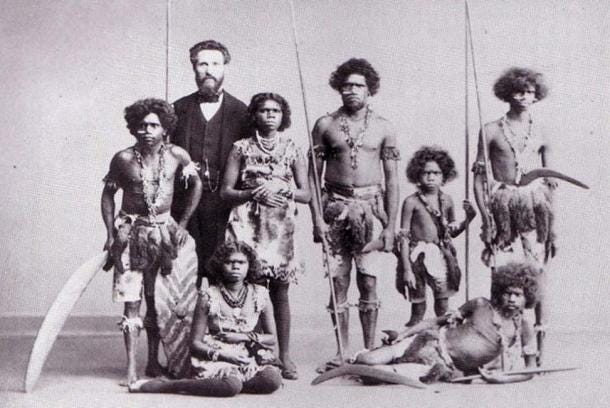

When we take into account the historical background, today’s views could be said to be healthier. In colonial Europe, at the time of Darwin, aborigines were considered sub-human, the biological ancestors of European populations, and closer to primates. Their languages therefore were deemed “primitive”, unrefined, only capable of transmitting the most basic ideas with very rudimentary structures.

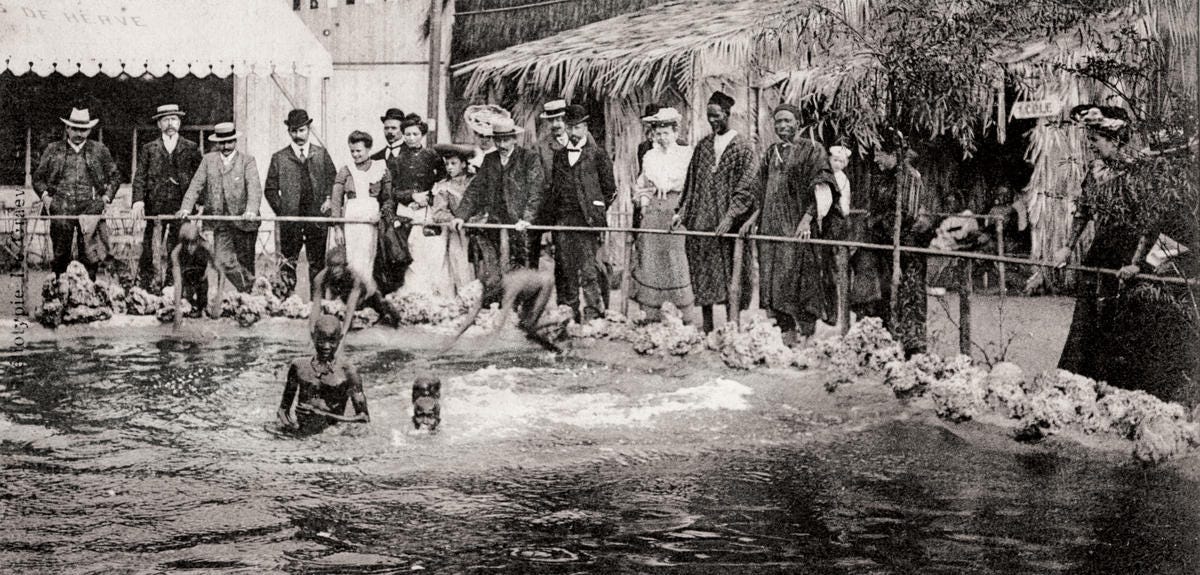

The pond of the “Senegalese Village,” Universal Exposition of Liège (Belgium), postcard, heliotype, 1905.

I think that we can all agree that that was prejudiced, racist, and fueled by the idea that Europeans were a “superior race”.

Australian Aboriginals captured in Australia and put on tour throughout Europe and America in the PT Barnum & Bailey circus, for its shows of ‘human curiosities’, where they were portrayed as fierce savages and cannibals (public domain)

But, once linguists started actually studying these “primitive languages” in conquered territories, they discovered that they actually contained a great degree of complexity. At least, some of them did…

Descriptivism

Thanks to researchers like Edward Sapir, Franz Boas and several others who took the trouble of actually studying those populations and languages (mainly from the Americas), it was finally acknowledged that those languages weren’t so primitive after all. Many of them show extreme complexity in their morphology (the way words are formed), their sounds or their richness of vocabulary.

Edward Sapir (1910)

These linguists were more open-minded than nowadays, and still allowed for different degrees of complexity. Sapir, for example, saw that all languages were not equally complex. He just didn’t believe that there was a correlation between language complexity and the level of civilization. (That is, some primitive peoples could have very complex languages, and vice versa).

As was common back then, they did not have any fears when describing primitive cultures as lacking expressions for abstract ideas, due to the fact that they were mainly focused on concrete things, on their everyday life. They often posited, however, that they were perfectly able to change their language IF the culture started requiring something other than a focus on the tangible here and now.

To my view, even if these theories were missing some pieces of the puzzle, they were way more accurate than what came later:

Generative Linguistics

In the sixties, there came the so-called Linguistic Revolution, under Noam Chomsky. His theory and scientific dogma is a subject for another article, but regarding complexity, it solved a problem (or rather, it pushed it under the rug.). Up until that point, one of the questions was whether the structure of a language reflected its society’s cultural level. Generative Linguistics posited that language structure was totally separate from human culture. For generativists, the language capacity is a “mental module”, a part of biology (not culture), the product of a GIANT mutation from ca. 150 thousand years ago. It is in the genes (which to this date, have never been found), and it is entirely determined by human biology. Chomsky’s famous and recurrent analogy is that of an alien observing all our human languages. To the Martian, says Chomsky, all the languages would look like one and the same at a deeper level, and their differences would be seen as merely superficial. Put in different words, all languages are the same in their internal structure (I-Language), and the differences are only like makeup on a face, the way that deeper structure is externalized into each specific language (E-language).

Noam Chomsky (2002)

But are the visible differences between languages as trivial as that? Well, that’s easily solved for generativists! They originate in a set of predetermined “parameters”, which each language picks, and which gives it a different outward appearance. For example, in English the adjective comes before the noun (“a beautiful tree”), while in Spanish it’s the other way around (“a tree beautiful”). But those are mere details for generativists. They see all languages as being equally complex in their deeper structure. The thought associated with these phrases is, supposedly, the same.

There is so much wrong with the above, that I will leave it for a future article. For now, let’s just say that this current in linguistics became so prevalent that except for “fringe” schools of thoughts, the idea that all languages are equally complex has survived to this date.

Paying reparations?

We could leave it at that, say that all languages are equal, “pay reparations” for past prejudices, and live happily ever after. If only it wasn’t for the fact that that path is quite unscientific, and, contrary to its moral defenders’ claims, does not do due justice to actual diversity. Both atheists and religious researchers enforcing the “all languages are equally complex” dogma actually put everyone in the same basket. As a consequence, we lose perspective on, and respect for the actual differences and variety among human beings and their respective languages.

If this article has made you feel smarter than most linguists, let me just remind you that there ARE some really smart ones3. But unfortunately, they are no different from other “experts” in the Academia, regardless of how intelligent and well-educated they seem to be: they have also been brainwashed by political correctness, materialism and “truths” that are taken as a given, and that have gone unchallenged since their very inception.

1 Hockett C.F., A Course in Modern Linguistics, New York, Macmillan, 1958, p.180]

2 Jackendoff, R. & Wittenberg, E., “What you can say without Syntax”, in Measuring Grammatical Complexity, eds. Newmeyer & Preston, Oxford University Press, 2014, p 66.

3 One of them, Geoffrey Sampson, actually inspired this article. See for example: “A Linguisitc Axiom Challenged”, in Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2009.

Recent Comments