I suggest that you read my previous post before tackling this one, although it’s not strictly necessary, and only to have the full context. In it, we introduced the idea that not ALL languages are equally complex, a topic that we will explore in detail in the future. You would be surprised to learn how much this little problem has had a detrimental effect on the study of language, and in particular, in language chronologies and the theories around language “evolution”. They are actually plagued by it! So stay tuned!

However, just because languages are not equally complex as a whole, it doesn’t mean that complexity can or should be ignored. One of my favorite linguists, Guy Deutscher1, expressed it as follows:

“There are many questions about complexity which deserve linguists’ full attention and best efforts; the evaluation of complexity in well-defined areas; the diachronic [throughout history] paths which lead to increases or decreases in complexity of particular domains; the investigation of possible links between complexity in particular domains and extra-linguistic factors, such as the size and structure of a society. All these and others, are important to our understanding of language. But the investigation of questions relating to complexity in language will only be hampered by a chase after a non-existent wild goose in the form of a single measure of “overall complexity”.

But before we go any further, you may be asking, if complexity IS important, but we cannot get an absolute figure to measure its total, can it be measured at all?

Complexity is… complicated

The debate is not unlike what would take place in other fields, such as biology. How can you tell if a tiger is more complex than a lion, for example? Or how do you measure complexity in the visual system, versus in the auditory one? It is usually a pickle.

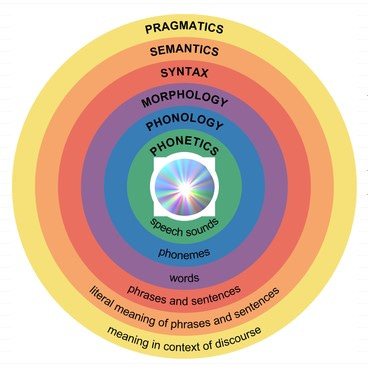

Traditionally, languages are divided into six main levels:

Although this is a useful generalization, and one that provides linguists with clear-cut and neat areas of research, one can easily see that these levels are interrelated. For example: the past tense formation could be said to be a part of morphology (the study of how words are put together). Yet, the only thing that creates the difference between “to fall” and “fell”, or “to look” and “looked” are tiny sounds (the subject of study in phonetics and phonology). So, where exactly is the boundary between sounds and words?

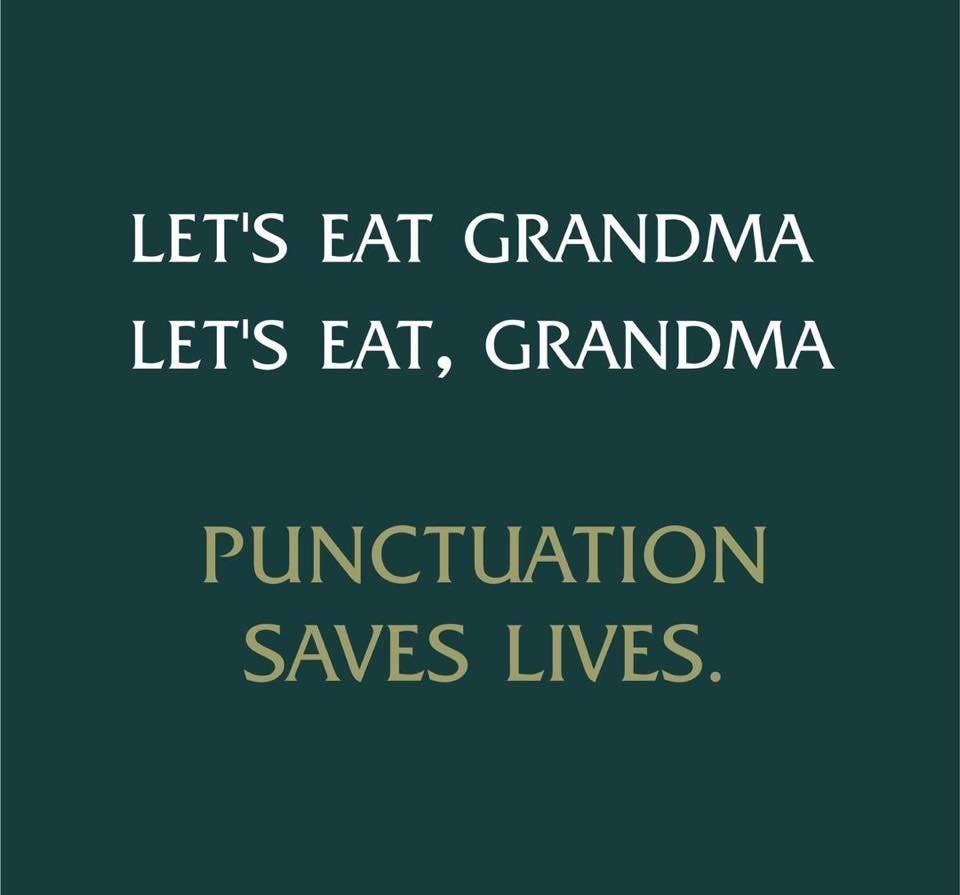

Or, take the difference between these two sentences:

The difference lies is one comma, which is technically part of syntax (how sentences are put together). Yet, it also has to do with pragmatics (language in context), since depending on the time in history and the culture you find yourself in, the second sentence might lead to a very bad outcome for “Grandma”. I recommend that you never visit such a place, even if your love for languages carries you far away…

This blurriness of boundaries does not only apply to levels that are close to each other, but can even jump across several levels. For example, the sounds of each language (phonemes) are believed to be arbitrary, devoid of all meaning (which would go into semantics, three levels above). This doesn’t seem to be true at all. If you are interested, I invite you to watch this series of videos, in which I describe different studies showing that sounds are not as “in-significant” as they seem!

These are just some examples of how complicated it is to separate a complex system like language into easily definable categories. There are no clear boundaries among the different aspects of language. In that sense, rather than being a set with different elements, language resembles an irreducibly complex system, in which, if you remove one part, the rest of the system collapses! (Watch the whole series below if you are interested in this particular topic).

But even then, there is SOME hope. As we saw previously, we all get a sense of how complex languages are, and in how many different ways. And there are different approaches that allow us to measure their complexity.

How to measure complexity?

Assuming that we are able to agree on the different levels or “parts” of language by using generalizations, and are at peace with not reaching the assumed “overall total”, how do we then go about measuring complexity? It requires several approaches:

1) First, we can measure complexity based on the number of “parts”. For example, how many tenses one languages uses, vs. another one. Or how many sounds one language has vs. another. This approach is used quite frequently, and can give you a general idea of language’s richness.

The problem only arises, once again, if you wish to reach “overall complexity”. In that case, we encounter the problem of assigning a “value” system to each of those parts. What is more important, the number of words, or the number of sounds? If language A has 25 sounds and an active vocabulary of 3,000 words, and language B has only 8 sounds but 10,000 active words, which one is more complex? Unless you make an arbitrary value judgment, you will be stuck attempting to come up with a grand total.

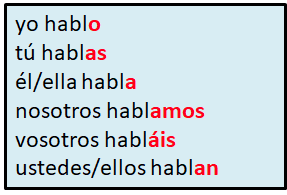

2) A second method involves taking into account the number of “parts” per single structure. This one is slightly easier. For example, let’s compare verb conjugations: how many endings do you need per verb, to specify tense, number and gender? Using Spanish as an example, the verb “hablar” (“to speak”) in the present tense has 6 different forms, or endings, depending on who is doing the talking:

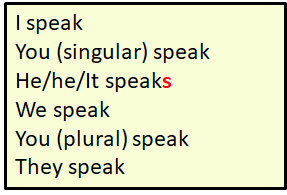

Compare that to English, where only the third person singular (he/she/it) changes, and with just a tiny “s”, so easy to remember:

If you wish to master all the conjugations, you need approximately 63 forms for each Spanish verb, while only a handful in English. It is easy to see that, at least in this regard, Spanish is way more complex than English.

A similar type of comparison can be made with grammatical cases, comparing languages that use them with languages that don’t. (I refrain from expanding on them at the moment, because I think you already get the main idea.)

This method is also useful. The problem, once again, only arises when trying to reach the unattainable “overall complexity”. How to judge which aspect (say, verbs), is more complex than others (say, nouns)? You see the problem, I hope.

3) Yet a third clever way of measuring complexity has been attempted, based on the amount of time it takes us to process language. In general, the more ambiguous and devoid of context a term or a sentence is, the longer it takes us to process it.

A famous example is that of the phrase “ayam makan” in Indonesian. Literally, it means “chicken eat”. But depending on the context, it can have many different meanings, such as “the chicken eats”, “the chicken is being eaten”, “the chicken will eat”, “if the chicken had been eaten”, etc. It doesn’t even tell us from the get go whether the chicken is doing something, or it is food. Expressions such as these are, on the surface, extremely simple. But it takes a person extra milliseconds to understand their exact meaning unless the context is obvious.

Another way to view this is that, quite often, what entails simplicity for the speaker leads to a heavier burden on the receiver, who needs more “processing power” to decode the message. Chinese, for example, has a very straightforward grammar. However, sound combinations are limited, leading to many words being pronounced in exactly the same way (with or without a difference in tone). In English you see that in pairs like “steel-steal”, “reed-read”. Now imagine that, multiplied by 10, and you get an idea.

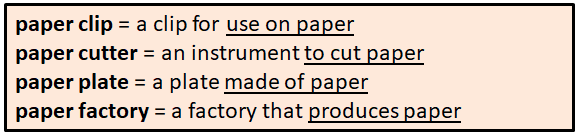

Within this method as well, you can measure complexity by analyzing the little games that languages play. English is fun in that way. If I tell you the word “paper”, you immediately form an image of what it means. But poor English learners struggle with terms such as:

See? You may not have thought about the different “roles” of paper, but that is quite complex for someone not familiar with this type of system.

When is complexity useful?

There are yet other ways to measure complexity, but I hope that you can already see how my original question was not easy to answer at all. Can complexity be measured? Yes, in individual areas, but not when chasing “overall complexity” and the magic “all languages are equally complex”. When used properly, complexity measurements show us that SOME languages ARE simpler than others in several respects. Indonesian has a simple grammar, and you can look and look, but you will not find areas where it “compensates” for that simplicity by having, say, a really rich vocabulary or sound system. The only “complex” aspect is what we saw above regarding vagueness for the recipient, but that is far from catching up to reach an equal level of complexity to, say, French. Russian has crazy grammatical cases, and its vocabulary is ALSO extensive, its verbs make you want to cry as a foreign learner, etc.

The only “simple” thing in it is that, except for a few exceptions, once you know the alphabet, reading is quite straightforward (as opposed to English with words such as “cough”, “though”, “plough”, “tough”). Even then, even if you can pronounce all the Russian letters, you still need to learn where the accent falls on each word, or you will be quite terrible at reading. Once again, complexity doesn’t add up to a neat shared total, but languages like Russian surely are complex.

There, now you know. We can now explore more fun (and important) aspects of language complexity, while keeping in mind that “All languages are equally complex” is a simply a myth. Diversity (different degrees of complexity) is important when comparing SOME aspects of languages, or two languages that are related to each other (e.g. old Norse and modern Scandinavian languages), and it can tell us a lot about how different humans view the world, organize their thoughts and societies, and what they have in common. It can also somewhat be useful when studying the history of languages (although in that field, I think it is overly used, to the exclusion of common sense). It is only when we refuse to see variations for what they are, and are afraid of even mentioning them because Academia will see it as “racist”, that we lose the ability to compare languages towards a productive goal.

1 Guy Deutscher, “Overall Complexity”: a wild goose chase?, in Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2009.

Recent Comments