Primitive Societies and Primitive Languages

In our last articles, we saw that the motto “All Languages are Equally Complex” (ALEC) is a myth, and described several ways in which language complexity can be measured. It is time to turn to another extremely controversial topic that, in my view, affects not only the entire field of Linguistics, but also our observations about what it means to be human.

What we discussed regarding language can be expanded to human beings: Are all societies (and individuals) equally complex? And is there a correlation between the level of complexity in each society and the language that they utilize?

What is a “primitive society”?

Although often considered politically incorrect in many anthropological circles, the fact remains that there exist “primitive” (or sometimes called “traditional”) societies, which share the following characteristics:

1. They are usually small populations, composed of several dozen to a few thousand members.

2. They live in relative isolation, hardly interacting with strangers.

3. Other than considerations of age and gender, they usually have a very low division of labor. Nobody is a “specialist” in anything, and each member contributes to the smooth running of the community.

4. Their technology is of a simple subsistence type.

5. Their social institutions are relatively simple.

6. There is usually neither literacy nor schooling. Children simply learn by observing, then joining in the adults’ activities. No direct instruction is provided.

7. Communication takes places almost exclusively in oral contexts.

8. Reciprocation is more common than money as a means of exchange.

Among these societies, there can be more or less complexity. For example, some of them don’t have any rituals or spiritual practices, while others do. Some don’t have any hierarchy, while some do. Some are hunter-gatherers, while others practice agriculture to different degrees. We will explore this further later on, but for now, you already have a good idea of what we are talking about. By “primitive” no moral judgment whatsoever is implied! It is simply what they have been traditionally called.

Language with Chu is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What is a “primitive language”?

If you are thinking that a primitive language must be very basic, you are probably imagining examples where you heard people speaking your mother tongue as a foreign language. “Me sleep here”, and such. In those cases, the problem is not their native tongue, but the fact that they have a very basic level in YOUR language. Imagine yourself dropped into Holland with no knowledge of Dutch, and only a dictionary to get by. Well, you too, would sound “primitive” when you ask for a room at a hotel: “Me sleep here?” would convey the message, but your Dutch would leave much to be desired. (This was, however, the way in which “primitive languages” used to be viewed, up until the sixties!)

Linguist Guy Deutscher writes:

If we define a “primitive language” as something that resembles the rudimentary “me sleep here” type of English – a language with only a few hundred words and without the grammatical means of expressing any finer nuances – then it is a simple empirical fact that no natural language is primitive. Hundreds of languages of simple tribes have now been studied in depth, but not one of them, be it spoken by the most technologically and sartorially challenged people is on the “me sleep here” level. […] Linguistic “technology” in the form of sophisticated grammatical structures is not a prerogative of advanced civilizations, but is found even in the languages of the most primitive hunter-gatherers. [i]

Ok, so we have way more complex systems in all languages, but are they all similar in complexity?

[That said,] two languages can both be way above the “me sleep here” level, but one of them could still be far more complex than the other. As an analogy, think of the young pianists who are admitted to the Juillard School. None of them will be a “primitive pianist” who can only play “Mary Had a Little Lamb” with one finger. But that does not mean that they are all equally proficient. […] it soon emerges that [languages] vary greatly in complexity of specific areas in their grammar. […] The more challenging question is whether the differences in the complexity of particular areas might reflect the culture of the speakers and the structure of their society.[ii]

So, the answer is, once again, that in specific areas, languages can vary greatly in complexity. But notice as well that Deutscher is not taking the more extreme view, that language directly affects culture and society (and thought), or vice versa. The key word here is “reflect”. I tend to think of language as a “magnifying glass” for some details of our reality, rather than about an entire worldview being determined by it. Languages may affect how we think about details and how we organize certain parts of reality in our minds, but they don’t change how human we are, and they don’t limit the thoughts we are able to have, if given the right stimulus or faced with the right needs. They just zoom in and out on certain aspects, and give us more or less freedom in others.

Just to give you a simple example, in English, if you say “Yesterday I slept at my neighbor’s”, your neighbor’s gender is not highlighted, and people can interpret your sentence as they wish. In other languages, where neighbors have obligatory genders, you are forced to specify if your neighbor is a he or a she, which might lead to your interlocutors making certain assumptions that weren’t there in English. That is the kind of “magnifying” that languages do.

So, back to Deutscher’s question, do the differences in complexity of particular areas of language reflect the culture of the speakers and the structure of their society? The answer seems to be yes. There are many correlations. What is not so sure is what causes them.

There are several ways in which to study this problem, and we will focus on two in particular, with the caveat that, as much as some “experts” claim that there is a clear-cut answer, nobody really knows! Perhaps language and society are closely linked, or perhaps it has to do with other factors that are often ignored in Linguistics, Anthropology, Biology and Psychology. So, remember the characteristics of a primitive society for the next installment!

[i] Deutscher, Guy, Through the Language Glass, Metropolitan Books, 2023, p.103.

[ii] Ibid, p. 103.

Language Complexity… is Complicated

I suggest that you read my previous post before tackling this one, although it’s not strictly necessary, and only to have the full context. In it, we introduced the idea that not ALL languages are equally complex, a topic that we will explore in detail in the future. You would be surprised to learn how much this little problem has had a detrimental effect on the study of language, and in particular, in language chronologies and the theories around language “evolution”. They are actually plagued by it! So stay tuned!

However, just because languages are not equally complex as a whole, it doesn’t mean that complexity can or should be ignored. One of my favorite linguists, Guy Deutscher1, expressed it as follows:

“There are many questions about complexity which deserve linguists’ full attention and best efforts; the evaluation of complexity in well-defined areas; the diachronic [throughout history] paths which lead to increases or decreases in complexity of particular domains; the investigation of possible links between complexity in particular domains and extra-linguistic factors, such as the size and structure of a society. All these and others, are important to our understanding of language. But the investigation of questions relating to complexity in language will only be hampered by a chase after a non-existent wild goose in the form of a single measure of “overall complexity”.

But before we go any further, you may be asking, if complexity IS important, but we cannot get an absolute figure to measure its total, can it be measured at all?

Complexity is… complicated

The debate is not unlike what would take place in other fields, such as biology. How can you tell if a tiger is more complex than a lion, for example? Or how do you measure complexity in the visual system, versus in the auditory one? It is usually a pickle.

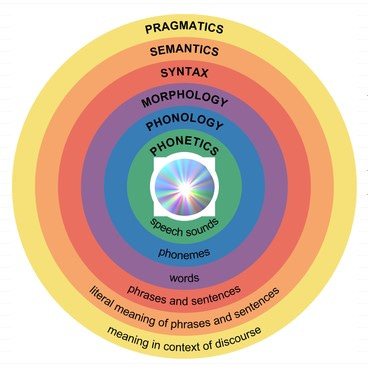

Traditionally, languages are divided into six main levels:

Although this is a useful generalization, and one that provides linguists with clear-cut and neat areas of research, one can easily see that these levels are interrelated. For example: the past tense formation could be said to be a part of morphology (the study of how words are put together). Yet, the only thing that creates the difference between “to fall” and “fell”, or “to look” and “looked” are tiny sounds (the subject of study in phonetics and phonology). So, where exactly is the boundary between sounds and words?

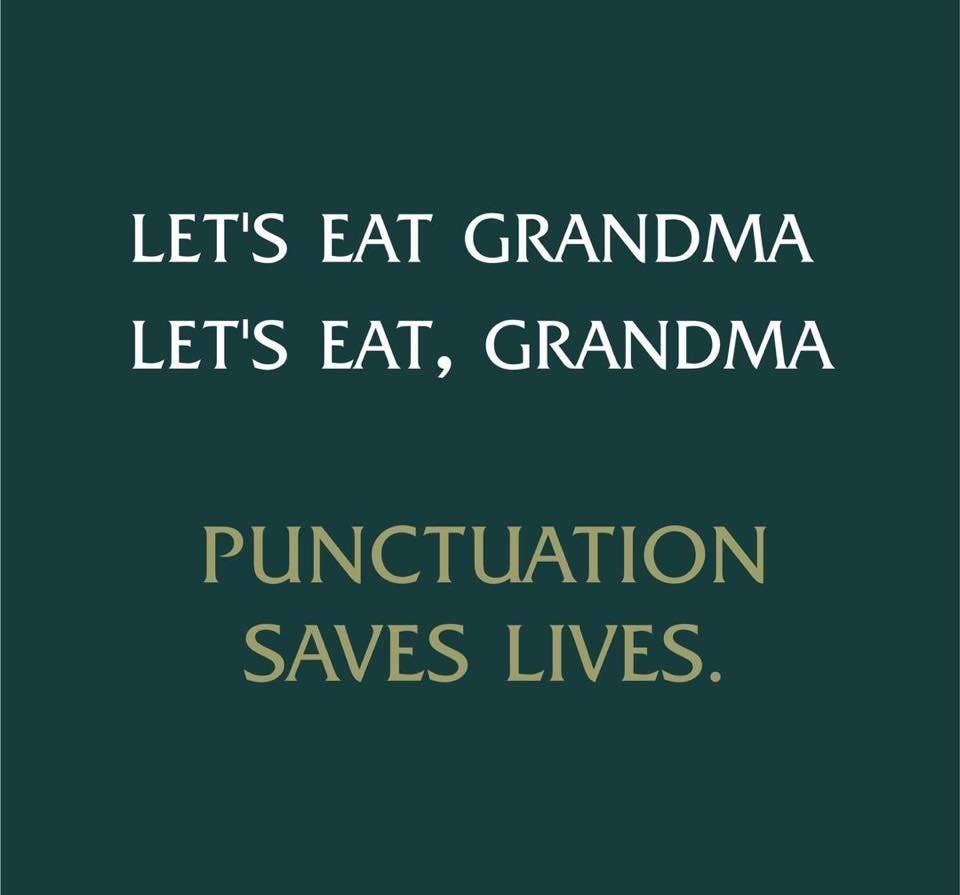

Or, take the difference between these two sentences:

The difference lies is one comma, which is technically part of syntax (how sentences are put together). Yet, it also has to do with pragmatics (language in context), since depending on the time in history and the culture you find yourself in, the second sentence might lead to a very bad outcome for “Grandma”. I recommend that you never visit such a place, even if your love for languages carries you far away…

This blurriness of boundaries does not only apply to levels that are close to each other, but can even jump across several levels. For example, the sounds of each language (phonemes) are believed to be arbitrary, devoid of all meaning (which would go into semantics, three levels above). This doesn’t seem to be true at all. If you are interested, I invite you to watch this series of videos, in which I describe different studies showing that sounds are not as “in-significant” as they seem!

These are just some examples of how complicated it is to separate a complex system like language into easily definable categories. There are no clear boundaries among the different aspects of language. In that sense, rather than being a set with different elements, language resembles an irreducibly complex system, in which, if you remove one part, the rest of the system collapses! (Watch the whole series below if you are interested in this particular topic).

But even then, there is SOME hope. As we saw previously, we all get a sense of how complex languages are, and in how many different ways. And there are different approaches that allow us to measure their complexity.

How to measure complexity?

Assuming that we are able to agree on the different levels or “parts” of language by using generalizations, and are at peace with not reaching the assumed “overall total”, how do we then go about measuring complexity? It requires several approaches:

1) First, we can measure complexity based on the number of “parts”. For example, how many tenses one languages uses, vs. another one. Or how many sounds one language has vs. another. This approach is used quite frequently, and can give you a general idea of language’s richness.

The problem only arises, once again, if you wish to reach “overall complexity”. In that case, we encounter the problem of assigning a “value” system to each of those parts. What is more important, the number of words, or the number of sounds? If language A has 25 sounds and an active vocabulary of 3,000 words, and language B has only 8 sounds but 10,000 active words, which one is more complex? Unless you make an arbitrary value judgment, you will be stuck attempting to come up with a grand total.

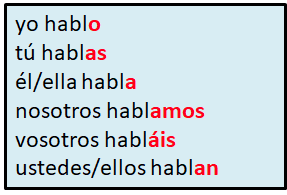

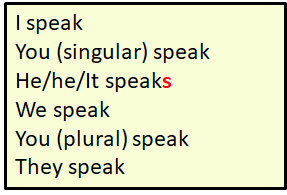

2) A second method involves taking into account the number of “parts” per single structure. This one is slightly easier. For example, let’s compare verb conjugations: how many endings do you need per verb, to specify tense, number and gender? Using Spanish as an example, the verb “hablar” (“to speak”) in the present tense has 6 different forms, or endings, depending on who is doing the talking:

Compare that to English, where only the third person singular (he/she/it) changes, and with just a tiny “s”, so easy to remember:

If you wish to master all the conjugations, you need approximately 63 forms for each Spanish verb, while only a handful in English. It is easy to see that, at least in this regard, Spanish is way more complex than English.

A similar type of comparison can be made with grammatical cases, comparing languages that use them with languages that don’t. (I refrain from expanding on them at the moment, because I think you already get the main idea.)

This method is also useful. The problem, once again, only arises when trying to reach the unattainable “overall complexity”. How to judge which aspect (say, verbs), is more complex than others (say, nouns)? You see the problem, I hope.

3) Yet a third clever way of measuring complexity has been attempted, based on the amount of time it takes us to process language. In general, the more ambiguous and devoid of context a term or a sentence is, the longer it takes us to process it.

A famous example is that of the phrase “ayam makan” in Indonesian. Literally, it means “chicken eat”. But depending on the context, it can have many different meanings, such as “the chicken eats”, “the chicken is being eaten”, “the chicken will eat”, “if the chicken had been eaten”, etc. It doesn’t even tell us from the get go whether the chicken is doing something, or it is food. Expressions such as these are, on the surface, extremely simple. But it takes a person extra milliseconds to understand their exact meaning unless the context is obvious.

Another way to view this is that, quite often, what entails simplicity for the speaker leads to a heavier burden on the receiver, who needs more “processing power” to decode the message. Chinese, for example, has a very straightforward grammar. However, sound combinations are limited, leading to many words being pronounced in exactly the same way (with or without a difference in tone). In English you see that in pairs like “steel-steal”, “reed-read”. Now imagine that, multiplied by 10, and you get an idea.

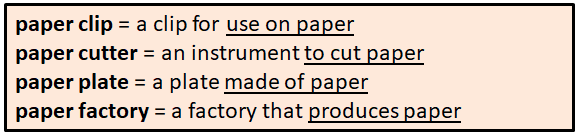

Within this method as well, you can measure complexity by analyzing the little games that languages play. English is fun in that way. If I tell you the word “paper”, you immediately form an image of what it means. But poor English learners struggle with terms such as:

See? You may not have thought about the different “roles” of paper, but that is quite complex for someone not familiar with this type of system.

When is complexity useful?

There are yet other ways to measure complexity, but I hope that you can already see how my original question was not easy to answer at all. Can complexity be measured? Yes, in individual areas, but not when chasing “overall complexity” and the magic “all languages are equally complex”. When used properly, complexity measurements show us that SOME languages ARE simpler than others in several respects. Indonesian has a simple grammar, and you can look and look, but you will not find areas where it “compensates” for that simplicity by having, say, a really rich vocabulary or sound system. The only “complex” aspect is what we saw above regarding vagueness for the recipient, but that is far from catching up to reach an equal level of complexity to, say, French. Russian has crazy grammatical cases, and its vocabulary is ALSO extensive, its verbs make you want to cry as a foreign learner, etc.

The only “simple” thing in it is that, except for a few exceptions, once you know the alphabet, reading is quite straightforward (as opposed to English with words such as “cough”, “though”, “plough”, “tough”). Even then, even if you can pronounce all the Russian letters, you still need to learn where the accent falls on each word, or you will be quite terrible at reading. Once again, complexity doesn’t add up to a neat shared total, but languages like Russian surely are complex.

There, now you know. We can now explore more fun (and important) aspects of language complexity, while keeping in mind that “All languages are equally complex” is a simply a myth. Diversity (different degrees of complexity) is important when comparing SOME aspects of languages, or two languages that are related to each other (e.g. old Norse and modern Scandinavian languages), and it can tell us a lot about how different humans view the world, organize their thoughts and societies, and what they have in common. It can also somewhat be useful when studying the history of languages (although in that field, I think it is overly used, to the exclusion of common sense). It is only when we refuse to see variations for what they are, and are afraid of even mentioning them because Academia will see it as “racist”, that we lose the ability to compare languages towards a productive goal.

1 Guy Deutscher, “Overall Complexity”: a wild goose chase?, in Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2009.

Language Complexity, Prejudices and Political Correctness

If you had to guess, would you say that all languages of the world are equally complex?

Most people reply to this question with a definite “no”. Perhaps they do so without the best of arguments, such as when they think that somewhere in the world, there are primitive languages at the level of “Me Tarzan, you Jane” (there aren’t). Or perhaps because they think that some languages are easier to learn than others, based on how similar they are to their native tongue (also not an objective assessment). Nonetheless, they would be right. And contrary to that, most linguists would say that the answer is “yes”. And they would be wrong!

For decades now, the consensus among linguists has indeed been that all languages are equally complex. That is, that what is less complex in one language (for example, its sound system), is bound to “catch up” for complexity in another area (such as syntax or morphology). For example, a language with only 10 sounds may have a very complex way of forming words. Thus, all languages maintain roughly the same amount of complexity. This idea stems mainly from what was initially a supposition, and never stated as a fact:

[…] impressionistically it would seem that the total grammatical complexity of any language, counting both morphology and syntax, is about the same as that of any other. This is not surprising, since all languages have about equally complex jobs to do, and what is not done morphologically has to be done syntactically. Fox, with a more complex morphology than English, thus ought to have a somewhat simpler syntax; and this is the case.1

You can find the quote above in many general Linguistics manuals, taken as a given. Even opposed schools of thought (such as those who believe language is mainly innate, and those who believe that it is mainly acquired) have one thing in common: none of them disputes that the overall amount of complexity is about equal in all languages.

Even when complexity within language systems is finally questioned, take any random introductory course on Linguistics, and you are likely to read something like:

“People think the same thoughts, no matter what kind of grammatical system they use”.2

That is, even if we admit that some languages are simpler than others, please don’t go imagining that some people are more “simple-minded” than others, or that their language limits in any way what they think about! This is quite welcome in the age of “diversity” and political correctness. But, step by step, I hope to show that whether we look at the problem from the point of view of language structure, OR thought, it is not quite so simple.

Language structure

The problem with assuming that the language structure is equally complex is that even a layman can easily discover that this is not true. Take German, for example: Its grammar is known to be more complex than English grammar, with cases, declensions, etc. But nowhere else in the language do you find something simpler than English. No “catching up” takes place. If the theory was true, German morphology (word formation) would be simpler than in English, for example, but that is not the case. Nor is the German sound system any simpler.

The opposite is also true with other languages, like the famous case of Indonesian (and most particularly Riau Indonesian), which is known to be simpler in pretty much every respect. It has a reduced number of sounds, a very simple grammar, very simple morphology, etc.

Language and thought

What about the idea that, regardless of grammar, people still think the same thoughts, as stated in the quote above? Once again, even if you have never studied any foreign language, you can see that that is not the case. A tribe in the middle of Papua New Guinea has no reason to be thinking about the complexities involved in building a skyscraper. They have no immediate use for it. And a New Yorker hardly ever thinks about how to hunt in the middle of the forest, because it is not within his or her immediate experiences. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t capable of doing so, as we shall see later, but it does mean that some people really think simpler thoughts than others, or at the very least, have very different habitual thoughts and ways of reasoning. And some habits can become so ingrained as to cancel others almost definitely. “If you don’t use it, you lose it”, as the saying goes. This does not have to be attached to any moral judgment or discrimination, unlike what many “experts” trying to shut down this debate would pretend.

Prejudice and discrimination in the Imperial past

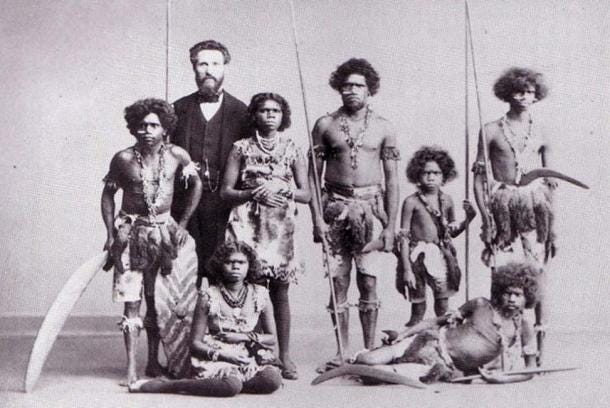

When we take into account the historical background, today’s views could be said to be healthier. In colonial Europe, at the time of Darwin, aborigines were considered sub-human, the biological ancestors of European populations, and closer to primates. Their languages therefore were deemed “primitive”, unrefined, only capable of transmitting the most basic ideas with very rudimentary structures.

The pond of the “Senegalese Village,” Universal Exposition of Liège (Belgium), postcard, heliotype, 1905.

I think that we can all agree that that was prejudiced, racist, and fueled by the idea that Europeans were a “superior race”.

Australian Aboriginals captured in Australia and put on tour throughout Europe and America in the PT Barnum & Bailey circus, for its shows of ‘human curiosities’, where they were portrayed as fierce savages and cannibals (public domain)

But, once linguists started actually studying these “primitive languages” in conquered territories, they discovered that they actually contained a great degree of complexity. At least, some of them did…

Descriptivism

Thanks to researchers like Edward Sapir, Franz Boas and several others who took the trouble of actually studying those populations and languages (mainly from the Americas), it was finally acknowledged that those languages weren’t so primitive after all. Many of them show extreme complexity in their morphology (the way words are formed), their sounds or their richness of vocabulary.

Edward Sapir (1910)

These linguists were more open-minded than nowadays, and still allowed for different degrees of complexity. Sapir, for example, saw that all languages were not equally complex. He just didn’t believe that there was a correlation between language complexity and the level of civilization. (That is, some primitive peoples could have very complex languages, and vice versa).

As was common back then, they did not have any fears when describing primitive cultures as lacking expressions for abstract ideas, due to the fact that they were mainly focused on concrete things, on their everyday life. They often posited, however, that they were perfectly able to change their language IF the culture started requiring something other than a focus on the tangible here and now.

To my view, even if these theories were missing some pieces of the puzzle, they were way more accurate than what came later:

Generative Linguistics

In the sixties, there came the so-called Linguistic Revolution, under Noam Chomsky. His theory and scientific dogma is a subject for another article, but regarding complexity, it solved a problem (or rather, it pushed it under the rug.). Up until that point, one of the questions was whether the structure of a language reflected its society’s cultural level. Generative Linguistics posited that language structure was totally separate from human culture. For generativists, the language capacity is a “mental module”, a part of biology (not culture), the product of a GIANT mutation from ca. 150 thousand years ago. It is in the genes (which to this date, have never been found), and it is entirely determined by human biology. Chomsky’s famous and recurrent analogy is that of an alien observing all our human languages. To the Martian, says Chomsky, all the languages would look like one and the same at a deeper level, and their differences would be seen as merely superficial. Put in different words, all languages are the same in their internal structure (I-Language), and the differences are only like makeup on a face, the way that deeper structure is externalized into each specific language (E-language).

Noam Chomsky (2002)

But are the visible differences between languages as trivial as that? Well, that’s easily solved for generativists! They originate in a set of predetermined “parameters”, which each language picks, and which gives it a different outward appearance. For example, in English the adjective comes before the noun (“a beautiful tree”), while in Spanish it’s the other way around (“a tree beautiful”). But those are mere details for generativists. They see all languages as being equally complex in their deeper structure. The thought associated with these phrases is, supposedly, the same.

There is so much wrong with the above, that I will leave it for a future article. For now, let’s just say that this current in linguistics became so prevalent that except for “fringe” schools of thoughts, the idea that all languages are equally complex has survived to this date.

Paying reparations?

We could leave it at that, say that all languages are equal, “pay reparations” for past prejudices, and live happily ever after. If only it wasn’t for the fact that that path is quite unscientific, and, contrary to its moral defenders’ claims, does not do due justice to actual diversity. Both atheists and religious researchers enforcing the “all languages are equally complex” dogma actually put everyone in the same basket. As a consequence, we lose perspective on, and respect for the actual differences and variety among human beings and their respective languages.

If this article has made you feel smarter than most linguists, let me just remind you that there ARE some really smart ones3. But unfortunately, they are no different from other “experts” in the Academia, regardless of how intelligent and well-educated they seem to be: they have also been brainwashed by political correctness, materialism and “truths” that are taken as a given, and that have gone unchallenged since their very inception.

1 Hockett C.F., A Course in Modern Linguistics, New York, Macmillan, 1958, p.180]

2 Jackendoff, R. & Wittenberg, E., “What you can say without Syntax”, in Measuring Grammatical Complexity, eds. Newmeyer & Preston, Oxford University Press, 2014, p 66.

3 One of them, Geoffrey Sampson, actually inspired this article. See for example: “A Linguisitc Axiom Challenged”, in Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2009.

Language Origins and Complexity – Part 8: Einstein has nothing on us!

What types of knowledge do you need in order to use language? You know A LOT more than you think! From abstract rules, to how to remove ambiguity in funny sentences, an ocean of knowledge is available to you every second of your day. Learn more about the ease with which you do amazing computations when you speak, and be proud of yourself!

TRANSCRIPT

Hello, and welcome to Language with Chu. If you haven’t watched the last two parts, please do so, so that you understand a bit better where we’re coming from, and getting to.

This part will be about the knowledge that is implicit, all the stuff that we need to know in order to use language. And it’s nothing short of a miracle, actually. So all these things, remember, are things that you’re not even aware of most of the time, okay? They’re implicit.

First you need to know sounds. And by sounds I don’t mean just /a/, /b/ etc, but also which ones correspond to your language, and how to combine them. You have all kinds of little rules in your head. For example, if I tell you “opened” and “looked”, both are the past tense of those verbs, but “opened” sounds like a “d”, the “d” at the end, while “looked” is actually a “t” sound. But you never thought about it, maybe, because obviously it’s written with “ed” at the end. Those have to do with sound combinations, what your language allows you to do. So you have a ton of rules just for that, for sounds.

Then you have a ton of rules of what I call “encyclopedic meaning“, because usually definitions in a dictionary are very simple, but they don’t convey all the subtleties and all the meanings of a word. Say the word “open”: you can open a door, open the closet, open a drawer, open a book, open your mind, open up with somebody, etcetera. There are a hundred of expressions with the word “open” that may not be in a dictionary, but you know perfectly well what they mean, and you use them perfectly well, and in a variety in multiple ranges of scenarios too. Okay.

Then you have knowledge about the word structure: if I tell you the word “teacher”, you know that it comes from the verb “to teach” and that the “er” means “a person who does something”, right? A teacher is a person who teaches. But what about “bestseller”? Is it a person who “best sells”? No. And what about a “villager”? Is it a person who “villages”? No. So, even though you saw certain patterns like in “teacher”, “carpenter”, “hairdresser”, etc., you already have knowledge of exceptions, basically. Of structures that are similar, but which don’t mean the same.

Then you have, based on word structure as well… you also have to expand into word order: in English, sentences go Subject + Verb + Object. So, if I tell you… a famous one for linguists is “Dog bites man” on a newspaper headline, for example. It wouldn’t necessarily make the news but what would make the news is “Man bites dog” because it’s more unusual. And you know which one is the subject and which one the object just from English’s word order. In languages like Hungarian, for example, you don’t have that at all, so you’d have to come up with other… you have to use other bits and bobs of the language to know who the subject is and who the object is.

And then you also have idioms: if I tell you, “He kicked the bucket”, either I’m talking about a janitor, say, who got really angry and kicked his bucket, or in most cases, you know exactly what I mean, right? It means “to die”.

Then there is the fact that you have to have these patterns —all these patterns in your head, thousands of them— and the abstract rules that go with them. Say the subject comes before the object, etc. and with just a few elements you form an infinite amount of sentences. It’s very likely that the sentence that I just uttered was never “invented” before. Some sentences are repeated and are very common, but for the most part, we can produce an infinite amount of sentences, with an infinite length, even, and still be understood. And nobody really knows how we do that, but it’s one of the nifty things about language, that with a few elements you can keep going on and on and on, just like I am now.

Okay, then you have the sentence structure. Like I said on the previous video, if I tell you “the woman standing next to you smiled”, did you smile, or did the woman smile? You know immediately that it’s the woman, even though “you” is right next to “smiled”. You just know how the thing works, and you understand the concepts in your head, and you can follow a conversation without any trouble.

Other examples are found often in newspapers, and they make for funny titles. I was looking for some earlier, and there is: “Students cook and serve grandparents”. There are two meanings there, and you got immediately what the right one was, but the other one sounds kind of… not too cool, right? Here’s another one: “Drunk gets nine years in violin case”. Obviously, it’s not the violin case, it’s a legal case, right? Or “Iraqi head seeks arms” obviously is the arms as weapons, right? [And the “head” as leader”.] So, all those little things make up for funny ambiguities and silly titles, but you know exactly how to use them. Immediately, you know how to recognize them.

And then finally there is “contextualization cues” which is anything you need to know about, say, for example, pronouns. In many languages, you have different pronouns according to the age of the person. Or even if I just tell you simply “you saw them” or “he saw them”. You know who “he” is, and you know who “they” are (“them”). Otherwise you couldn’t understand that sentence, and I know you know. That’s why I’m using these pronouns.

So, basically, if you combine all of this with the knowledge about your environment that you need, which is a lot… You need to read cues all the time (nonverbal communication). You need to know others, you need to know how others think more or less, you need to know who you’re talking to. You need to know everything about the world that you can know, from gravity to how to buy potatoes at a supermarket. Anything, everything that you know, it weighs more than an entire encyclopedia in your head. And yet, you just use it as if it was nothing. You take language for granted most of the time.

So I’ll finish with this: if you ever think that you’re too dumb, too old or whatever to learn any new language (or any new skill, really), just remember how much you know about language, and with how much ease you use it without realizing it. If you’ve managed to learn your mother tongue and anything else in life, you can tackle your next project, no problem! You’re going to be able to, because any time we acquire a complex skill such as language, we’re picking from all kinds of areas (physical, mental, and social) to perform all kinds of functions. And we have a ton of abilities that we don’t even remember we have or acknowledge that we have or notice that we have.

So you’re just a walking little Einstein (we all are) when it comes to language. And yeah, to me it’s like magical. It’s amazing. The richness of language is unbelievable, and we often take it for granted just like we do for most of our other capacities, or even the parts of our…. how our body works as a whole.

Thank you for watching, for leaving comments and questions and likes and for subscribing, and see you soon for more on language!

Language Origins and Complexity – Part 7: What does Language Do?

And now we explore all the functions that language fulfills. Our lives would be so empty without it! Language is constantly helping us communicate, understand the world around us, and even ourselves. It can be used for creation, or for destruction. A few words can become powerful actions. And last but not least, language offers a window towards what is invisible in the miracle of life. Are you still thinking that we owe language to gradual and random mutations? Think again!

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello, and welcome to language with Chu. Let’s continue on with what language is. I recommend that you watch at least part six of this series, if not all of it, so that you have a pretty good idea of what we’re talking about.

But now, on this part, we’re going to focus on what the functions of language are. What does language do for us? Well, there are many, many functions. You can you can do as we did in the previous one, if you want. Pause the video and try to come up with your own ideas of what language does, and then tell me if you got more or less than I did.

First of all, we have a communicative function. For linguists, sometimes communication is the most important function of language. For others, not so much. Rather, it’s more like an expression of our thoughts. Both camps, again, are right in a way, but I think they also miss a lot of details. But if we only focus on communication, we could say, well, language serves to express ideas, concepts, feelings, thoughts… anything you want to can express via language. And if you didn’t have language, well, good luck expressing some things! If I wanted to tell you that yesterday I tripped and fell, and my knee was aching, I could probably try to imitate the action, sort of, and you might get it. But imagine if I was telling you without language that I’m reading this interesting book about gravity, and blah, blah, blah. Good luck with that, right?

So language fulfills a big, big function in terms of expressing our thoughts, our feelings, or any concept, really. And how do we do that? Well, we do that with symbols. Again, there are different schools of thought. Sometimes linguists prefer to talk about a “language of thought”, which works with different grammar rules, if you wish. And different symbols too. And then we have language as it is externalized/ expressed via your own mother tongue or other languages.

But now, for the sake of simplicity, let’s just focus on the symbols that we use for language. And those can be of all kinds. The sounds, like I described in the Sounds and Meaning videos. It can be morphemes: “possible”/”impossible”. The “im” in “impossible” means “not”, “not possible”. You know those things without even thinking about them.

Then comes each word. You have to know the symbol for each concept, each word. So you know “yesterday”, “bottle”, “tree”, “cigarette”, or anything.

Then you know groups of words. You know that “behind the sofa” is three words, and it’s not the same as “in front of the sofa”, while for a foreigner, for example, that might be all a blur and they don’t know where one word starts, and the other one finishes, right? For each of the languages we master, we know how to decode and encode groups of words.

Then we have groups of clauses, that is, many sentences within sentences, and full sentences. So, for example, if I tell you, “The man who worked at the flower shop loved the lady who worked at the bakery”, or whatever, those two chunks of sentences… the “who worked at the bakery”… are closest, and you know how to group them. And you know how to understand immediately a sentence. Or “The teacher standing next to the pupil smiled”. Who smiled, the teacher or the pupil? You immediately know that is the teacher, right? Even though “smiled” is right next to “pupil”. So all those things are automatic for you.

And then we have this idea that for each symbol, you have a form (whether it’s the letters in the way it’s spelled or the sounds in the way it’s pronounced), and you have a meaning (what it really means, kind of like a dictionary definition). But as we’ll see in a minute, meaning is not so simple. It’s a lot more complex than that. And the sign, the symbols, may not be as arbitrary and conventional as it’s often thought. Usually it’s believed that somebody (our ancestors, the people who created our own language) decided, “Okay this is a paper. You know this is called paper end of story”. Everybody starts calling it “paper”.

Well, if you watched the Sounds and Meaning videos, you know that it… I think it can’t be that simple, because there are too many similarities across languages, even in languages that are never supposed to be related. That speaks of something else, that speaks of some kind of glue that binds certain groups of languages with others, and that it’s not as easy as to say, “Well, this is the mother of this language”. I’m going to make another series on the chronology of some of the languages and how supposedly they evolved. Say, romance languages from Latin. And you’ll see that it’s not so clear-cut. I don’t have the answer, but I think it’s a lot more, I would say “spiritual”, in a sense. It’s not so tangible, it’s not so easy to determine as to say it’s just conventional, somebody decided and everybody agreed, okay?

So next: the interactive or social aspects and functions of language. Many things in language are actions. They’re called “acts of speech”. So, if I tell you, “Pass me the salt!”, it really is an order. If I were a minister and I were to tell you, “I pronounce you husband and wife”, think of the implications of that, just that little sentence. If I ask you, “Do you know the time?” Obviously, I’m not asking you if you know the time, but I’m asking you for something. And if you’re a smart ass, you could say, “Yes I do, and not answer my question, but you know what I mean. So all those are acts of speech.

Then you have something that I think is quite important in language. I’ve mentioned it in the past as well, and it’s that language, as much as it allows us to express our conscious feelings and thoughts, it also allows for more sneaky feelings and thoughts, and it can be turned into a weapon for creation or for destruction. Simple words like “pandemic”, for example. The definition has changed a lot in the last two years depending on who you ask, what “science you follow” and… I don’t want to get political or anything, to not be banned from Youtube, but I hope you get my meaning.

Other words like such could be “white male”, “dissident”, “war on terror”… It all depends on who’s telling them, and who’s using them for creating policies that could either improve the situation in a country or destroy it, improve the situation in society or destroy it, create more division or not. So I think that’s an important function of language that usually gets exploited. But not always. Sometimes it’s used for good reasons too, kind of like when you give yourself good affirmations and you accomplish something after the fact.

Then we have that language fulfills a role within culturally understood activities, with mutually understood goals. What I mean by that is that, for example, say you meet with a bunch of friends and it’s agreed that you’re gossiping, that you’re not really telling the truth about somebody, or really have solid proof about what you’re saying. Everybody understands that, and that stays within the context of that conversation. Or say you go to a shop to buy a pair of boots. If the shop assistant suddenly brings you a bundle of bananas, you know that there’s something wrong, right? It doesn’t belong to that kind of situation. So language has to keep… when you’re using language, you keep in mind all those kinds of goals and activities and rules.

A then, finally, you get a lot of information from language with cues from your environment. So, an example would be, again, that one about the bananas instead of shoes. Or when you get cues about how the other person is feeling, and you change the way you’re talking, because you’re getting those cues from his or her language and from the environment as a whole. So language uses… it filters a lot of information that you constantly are bombarded with.

And finally, this is a little bit less, let’s say, “official or mainstream”, but I think language is a big, big tool to make sense of our world, from when we’re children till much later too. The words we have are an integral part of who we are, of our growth, our internal world. It would be nice to have, say for example, telepathy. I wouldn’t have to guess your thoughts, and you wouldn’t have to guess mine. But would we learn as much? When you’re trying to express a strong emotion, and you don’t have the words for it, and you search and search, and dig, and finally go, like, “Yesss! Eureka! I know how I feel. I can tell you”.

All those things have to do with finding words, with using language, and I think they’re a part of our ability to grow as human beings. They’re also part of our… without language, we wouldn’t be able to listen, and learn to listen to others, which is very, very important to grow something in us, to grow more empathy, to be able to develop deep relationships, etc.

Then there’s also a lot of language that has to do with our growth, or our internal world, in terms of that inner dialogue that we have, sometimes. You know, for example, you’re trying to achieve something and you go, like. “Oh no, I’m stupid. I’ll never achieve this”. Or, “Like my mom used to say, I’m gonna be useless at this”, or whatever you’re thinking that you carry from childhood. And all those things use language. You’re talking to yourself most of the day, actually, more than you talk to others.

So they’re all part of our internal world and, like I said before, it’s also (in terms of our how we cope with reality) it can also be said to be an engine for creation or destruction depending on what we tell ourselves, what we conquer in ourselves, etc.

And this one a debated one: language is reflective of our perception, it has to do with thought and the question of “how much does our culture influence our language, and vice versa?” How much does our language influence our thoughts. That’s another topic for another series of videos, because there’s a lot of interesting stuff to tell you about it that you probably don’t know.

But basically, all of this has to do with thought, whether it’s a language of thought (like some linguists believe) or if thought is something separate. We use thought a lot when we use language, and language a lot when we use thought. The only difference is that when you speak it or write, it adds some kind of linearity to it. You could think in many terms, think of many things at once, but you can’t vocalize many things at once.

And then, again, debatable, is the idea that language forges habits of mind. It forces us to think about some things and not others. For example, if in English I tell you, “I spent the night at my neighbor’s house”, you don’t know if my neighbor is a man or a woman, if I’m trying to tell you something without saying something, or whatever. While in Spanish, I would be forced to tell you immediately whether my neighbor is a girl-friend or a male friend, see? Because Spanish is a gendered language, and “neighbor” is either masculine or feminine. So I would HAVE to add that information and all those little things. That’s just a small example, but all those little things may forge something in our minds that makes us view the world in slightly different ways. Sometimes not so slightly different, actually.

But that’s a topic for another video, and I would like to hear from you on the comments if you thought of any other functions that language has, and if you agree with any of this or disagree. And which one you think may be the most important one if there’s any. But I hope that now with this video and the previous one, and all the previous ones, you’re seeing how complex it is, how a simple definition of “language is just a means of communication” doesn’t really begin to describe what language is.

And I hope you see that it’s also very difficult to determine what we’re born with, and what we learn as we develop, as we grow. So I’ll leave it here and see you on the next part. Leave me your comments and please subscribe to my channel, and click on like and all the things you do on Youtube and share farm wide if you find this interesting. Bye!

Language Origins and Complexity – Part 6: A huge set of skills combined

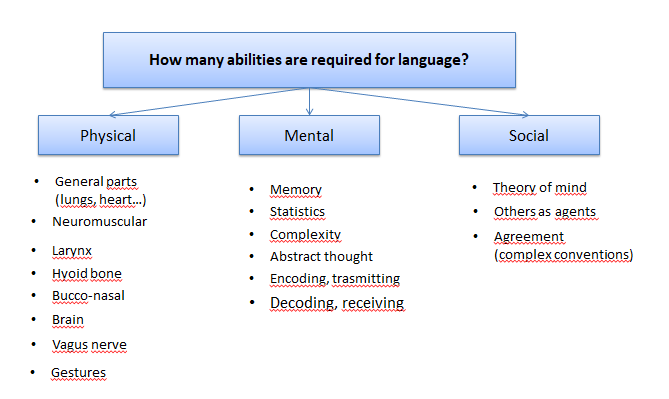

I’m back! This one may be a bit more “nerdy”, but it explains some things about language that you may never have thought about. You’re a genius for speaking any language! ![]()

If you are a language nerd, you will like this one! How many parts of our bodies do we need to produce speech? Which is the only floating bone in our body, and how is it useful for speech? How do we use statistics all day long when producing language, and not even realizing it? What is Theory of Mind? What abilities do we need to put to use every time we speak, ranging from motor skills, to cognitive abilities and social aptitudes? All this and much more, to explain how everything in language is complex, and how its basic dictionary definition doesn’t even begin to explain it.

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello! And welcome to Language with Chu.

Today we’re going to talk about something very simple, actually. Yet, I hope to show you that it’s a lot more complicated than it seems. If you’ve watched my previous videos about Sounds and Meaning, and about Language Complexity you already have an idea of where I’m trying to get to.

But I’ll start with the simplest question of them all: What is Language? And by working on that definition I hope that it’s not too nerdy and that you get a lot of ideas about how language works, and why the state of Linguistics, or the state of the “science of language” is kind of stagnant nowadays.

One of the problems is that, like in any science, most people try to find a very simple definition for something, so that the hypotheses that they are testing will make sense, will be able to be tested even, and the experiments replicated, etc. Well, Linguistics is a little bit in between, because it’s within the Humanities, but some currents of Linguistics have been trying for decades to make it more scientific.

So it’s a little bit between both sides, and you can forgive some linguists for being too “scientific” and missing the forest for the trees, or some others for being too “wishy-washy” in their definitions. But the problem is that, with language, I think, you can’t just focus on one simple definition. In fact, I hope that in the examples that come next, you’ll see that everything in language is complex, and everything in language requires more than one dictionary definition.

Ok, so, let’s start with “What is Language?”. If I were to ask you how many abilities you need to speak, and to use language in general… And here, just a note: When I’m talking about “Language”, I’m talking about the Language capacity, not each individual language, ok? So, what do we need to know from a physical point of view, from a mental or cognitive point of view, and from a social point of view? What is the set of skills that you need in order to speak? And I would suggest that you pause the video here, and think about it. Make you own little bullet points, and then resume watching, and see if you got them all. I probably missed many, but I think you’re going to be surprised. [Pause].

Okay, I’m assuming you paused the video and did that little exercise if you felt like it, but let’s start with the physical things that you need to have and to know: First of all, you have to have “parts” that work. You need to have lungs to breathe, you need to have a heart… If you’re not alive you’re not going to be talking! You need a functioning brain… You need everything that makes you a human being to talk.

That’s number one, and they need to work FOR language. For example, our breath is used in a specific way to materialize language. Otherwise you could just be breathing without making any noises, any vocalizations, and it wouldn’t be called “speech”.

Second, you need a neuromuscular complex, I would say: we have roughly 700 muscles in our bodies, and about 78 of them are muscles that we use for speech. Not just for speech, but mainly for it. So, that’s a lot! And you need every tiny muscle and nerve and everything to help you articulate the sounds you make (produce sound), they need to help you control how you articulate things (otherwise nobody could understand you), and they have to make it as easy as possible for you to produce sounds.

So all of that is an entire mechanism working in the background while you use speech. You have a lot of skills you don’t even realize you have, because they are subconscious [automatic], basically.

Then you need the larynx, and the larynx is basically the “voice box” that we have (some people call it the voice box), but it’s just 2 inches long, it’s not very big. And without it, we couldn’t speak either. But the interesting thing is that it’s involved in many functions apart from language. And you’ll see this more, and more, and more. There is hardly any unique thing that we could say, “this is ONLY for language”. For example, we use the larynx, all this part of our necks to swallow, to breathe, to cough… and there are minute mechanisms going on in the larynx to allow you to talk, or to swallow, not to choke, etc. So you need the larynx.

You also need something called the hyoid bone. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it. But it’s this floating little bone, kind of inside here… You cannot really palpate it, but it’s studied nowadays for problems with sleep apnea. It’s used in forensics for determining of somebody was strangled or not. And as a funny piece of trivia, I’ll let you that if anybody asks you, “which is the only bone in the body that floats?”, you can say it’s the hyoid bone. It’s not quite correct, because it’s floating on air, but it’s a bit like the patella, the knee cap. But this one is particularly… Here in the image you can see how it really looks like it’s floating. It’s connected by a bunch of ligaments and little muscles and stuff, but it doesn’t articulate with any other bone. So that’s why it is said to be floating.

Well, this little bone is interesting because it is in the right position to help the tongue move, to help the larynx open and close so that you can speak, or swallow or eat….

And animals have it… animals have a larynx too (many animals), but they don’t have them in the right position to allow for speech. It’s commonly believed that one of the things that made humans speak [in the course of evolution] was the descent of the larynx. In some animals it’s very, very high, so it doesn’t allow for the cavities that we have. Resonance cavities and such. And there is not much difference between the sounds that they can produce for vocalization, and the piping for eating or breathing. In our case, humans, our larynx is quite low and that creates enough room, levers and pulleys that allow us to do both: breathe and eat, and speak. But, I can tell you right now that that’s not really true, because many animals also have a lowered larynx, and it’s not because of that that they speak. So, it can’t be the only factor. None of these are the only factors, but they all contribute to speech.

You also need a bucco-nasal cavity. So, anything that resonates, from your nose, to your cheeks, to everything in your mouth, your teeth, etc. In my videos about phonemes and sounds I described how each sound in language is placed in the mouth, and they each have their names, etc. If you are interested, check that video too.

And then you have a brain. Obviously, you need to have a functioning brain. And again, there is so little that is known about it! You will hear that Broca’s area, or Wernicke’s area is for language. And although there is some specialization and language is mostly seated on the left hemisphere, there are many cases of injuries where the brain immediately kind of takes over, or compensates for the part that is injured and uses something else.

So, I don’t think it’s as simple as saying, “Here is my language center”, or whatever. Not to mention that, as we’ll see in a minute, we need so many skills to speak and to use language, that it seems that the whole of the brain is lighting up when we speak. Also, the studies that we CAN do nowadays, with brain scans and MRIs… They are quite limited, if you think about it, because all they are showing is brain activity as in electricity, and maybe some neurochemicals acting, and chemical activity. But it’s not the whole banana, because where is it all stored? How does it work? The amount of words you know, the amount of knowledge you have about the world…

I had an MRI done once, and my brain looked quite tiny, you know? And I speak three languages really well, and three others not so well, and I have no idea of how it could all fit into my small brain. Maybe you have a bigger brain! 😉 Anyway, I don’t think that explains language and how it works. I think it has more to do with the connection between brain and mind, so everything that is non tangible but that is usually equated with the brain.

Okay, and finally (I’ll go through these quickly), you need the vagus nerve. I’ve spoken about the vagus nerve in previous videos too. What is interesting is that, as I just said, the brain is not everything, and the vagus nerve, not only does it have the right branch that controls, or helps you regulate a lot of your facial movements, but it also has a very important pro-social role. And also, it reaches all the way down to your gut. Recently, or not so recently, scientists found out that 90% of the branches of the vagus nerve send signals up to the brain. And do you know what also is in the gut? Neurons. There are a lot of neurons. So again, nobody knows how we think, how we feel. Maybe most of the time we’re thinking with our guts? I don’t know. Anyway, you need that to speak as well.

And you also need gestures. For many linguists, gestures are at the beginning of the emergence of language. I don’t quite agree, and if you’ve watched the previous videos in this series, you know why. But gestures (gesticulating) is important for language, and the more you know who to use them, the more you can use them, the better for language.

OK? So that’s it for what you need to do physically, and if you notice, all of this is almost subconscious, or you don’t really have a lot of control over it. You’re not thinking, “I have 78 muscles in my face that are helping me produce language”, right? If you think about it, you might say so, but most of the time we use language spontaneously, without giving any of these things a thought. OK? So, I would say that this is part of the definition of language if you include what is required for language.

Next we have anything that is cognitive. So, what do we need in our brains or our minds to use language? Well, you need memory. And memory of several kinds. You need short-term memory. Because, say you forget everything I say 3 seconds after I’ve said it. You wouldn’t be able to watch anything, to listen to anybody, you wouldn’t be able to keep your train of thought, etc. You need long-term memory to remember all kinds of things about the environment, about the social situations, about a text, for example… Everything in your long-term memory helps you understand language, more so than we often think it does.

Then you need something kind of nifty, which is statistics. And we are all kind of experts at statistics, if you think about it, because when you learn a language, there are things that are allowed, and not allowed. When you listen to a foreign language, there are sounds that just don’t sound English to you, right? Why? Because you are doing all kinds of computations in your head that tell you, okay, these sounds are normal/allowed in English.

Not only that, but these sounds can also be combined in a specific order in different ways, and when you shuffle them around, they just don’t sound English anymore, right? Well, all those things are a kind of statistic work, because you are always working on probabilities. When you listen to somebody, your brain is calculating, “Does that make sense? Is this more likely than not?” And if it is more likely, then I can even not hear the sounds, and make up the word: If I tell you, “I like ‘omputers”, you didn’t hear the “c”, and maybe you didn’t even notice you weren’t hearing the “c”. “I like ‘omputers”. And you kind of made it up, because you know that, statistically, “omputer” is usually preceded by a /k/ sound.

OK, and that shows that there is a HUGE amount of complexity in what we say. We use language all the time, and it’s so easy, or it sounds so easy to us… It’s only when we meet somebody who is learning our language, our mother tongue as a foreign language that we realize how hard it is. And we don’t even realize all the knowledge we have.

For example, if you are a native speaker of English, could you conjugate the copula in the third person plural, simple past? I’d be interested in hearing how many of you did it, if you can post a comment. What I just said may have sounded like Chinese, but it’s just “they were”, as in “they were happy”. The verb “to be” is called the copula in linguistic jargon.

Or if I tell you the verb…. Give me the verb “to look” in the second person singular, in the present perfect. Can you do it? “He has looked”, or “She has looked”, or “It has looked”. So, see? I know that because I learned English as a second language, but you don’t need to know that. You have all these rules… phonological rules, morphological rules (so which word chunks can go together with which ones)… you know all the verb tenses, you know how to put sentences together… All those things, you have no idea how you do it, but you know it. And when some “annoying” foreigner starts asking you, “but why did you use this tense instead of that other one, blahblah”, you go like, “I don’t know, I just use it!”. So, there is a lot of complexity in what is going on in your mind.

You also need abstract thought, obviously, because not everything is concrete. You need abstract thought even for having a conception of time when you are speaking. You need abstract thought for everything, basically when you speak. It would be very hard to only focus on concrete thoughts to be able to have the type of communication we have nowadays.

And then you need a whole apparatus of encoding and transmitting: so, I’m encoding information and sending it to you; you’re decoding it and receiving all the information. Nobody really knows how that works. There is Information Theory based on some of these concepts, but from there to know how it works in the brain… Scientists have tried, and keep trying to find out how it all works, but like I said, there is so much that we have inside our brains, that it is very difficult to know why, and how language really happens.

OK, and then finally, from a social point of view, you need something that is quite human, although some animals have it to a certain extent too. And that is “theory of mind“. And “theory of mind” is just a term for describing when you can ascribe a mental state to somebody, and predict their reactions, and adjust your own behavior. So, say I tell you, “Hi! How are you?”, and you say, “I’m okay…” [with a sad face]. I already know from your expression that you are not really doing ok. So I can’t take you literally, and I may as you, “What’s wrong?”. Or when I’m about to make a request, if I’m a little nervous I may be trying to figure out first if you are in a good mood, if you’re not, etc. So, all those things are “theory of mind”, and in language it’s super important because we read a lot of non-verbal cues, sometimes more so than words.

Then, there is something that goes with it: we also have to take other people as agents. If you imaging that people are talking for the sake of talking (some people do, but…! 🙂 But if you imagine that nobody has anything to say, then you wouldn’t try to find meaning in a sentence. And because we see that each person is an agent of communication, we try to find meaning, we try to express meaning, we try to be clear, etc.

And finally, we have to agree tacitly, and also subconsciously many times, to a HUGE amount of conventions in language. You have like a whole rule book inside your head that tells you “This comes after this”, or if a person says “hello”, I respond, etc. You know that if I tell you, again, “How are you?”, and you tell me “The sky is blue”, I’m going to think that there is something wrong with you, right? It’s completely out of context. So, there are all kinds of social norms. In some languages it’s even more important when there are different personal pronouns, for example, depending on the social rank of the person, or the age, like in Japanese.

And all those things, you are doing within a millisecond. You are processing A LOT of information. All of this, basically, that you see on the screen, is working at the same time, every time you say anything. Practically anything.

And what is interesting is that, like I said on previous videos, these parts weren’t really designed FOR language, or don’t seem to have been designed for language. Because if you take any of those physical, and mental, and social traits or abilities, you could say that they are part of a much bigger cognitive complex, or you could say that they are part of a much bigger network of functions that we fulfil as human beings. And each of the little parts, physical or not, allow you to do a multitude of things, not just speaking. So that’s a bit puzzling when you are talking about evolution, because, well, which one came first, if we need them all at once?

Then, from a more cognitive point of view, language is integral to our lives, I think. There are cases of children who were born and left in the jungle, or from sadistic parents who left them locked up in an attic, for example, until they were teenagers and they were found. And you can see in those children that they actually don’t have, not just language, but they’re also missing a lot of other cognitive and social abilities that your average Joe has. So, I think that language has a lot to do with our general development. It’s not just a system of communication, as it is normally described.

And then finally, an interesting bit about language is that it is completely blind do demographics, to social status, to anything. You can speak differently, but every human being (except for exceptional circumstances like I said before)… every single human being has at least one language. In fact, monolinguals (just one language) are a minority in the world. Most people can learn 2, 3 or 5 language with no problem, from birth.

So that’s it for the abilities required in language. I hope it’s not too “nerdy”, as I said, but just think about how smart you are if you ever are in doubt, for being able to do all those things at once.

And here you can see why there is a debate between the camp that says that we are born with it all, because it’s so complex that we could never have learned that in such a short amount of time when we were children; and the others that say that we learn it all. That obviously we were born with a certain ability for speaking, but that learning has a lot to do with it. And well, the two camps sort of fight with each other. I think both of them are right, and both of them are wrong in that they limit their definitions.

We will hopefully talk about that in more detail later. But yes, we’re born with a certain capacity for language, for sure. And our environment is very important. But just saying that you were born with it doesn’t mean that it’s all in your brain or your genes. In fact, there hasn’t been a lot of progress made in that respect. And just because you say it’s social and it’s learned, it doesn’t mean that it’s only the caregivers that teach language to a child that will have the only say in how it’s done, or that will provide the biggest amount of input. I think it’s a lot more complex than that.

This is just the first slide, so I talked a lot, I think! But anyway, I hope you liked it. We’ll stop here for this “episode”, and we’ll move onto language functions next. So, what does language do? And the types of knowledge that you need to have. Hopefully then to move into these kinds of myths that exist around linguistics and around the idea of language, and which ones we can rescue, and which ones should really be tweaked a bit so that they match reality, finally.

OK, so let me know in the comments if you thought of other abilities that are required for language, if I missed any important ones (I was just trying to summarize), and if YOU think that language is innate, or if we learn it. See you next time.

Language Complexity – Part 5: Funny Theories of Language Evolution

Have you ever heard of the “ta-ta” or the “yo-he-ho” theories of language evolution? These and several others started off as jokes, yet, you can find them mentioned in serious textbooks nowadays. It is as if most of the mystery of language’s origins had been relegated to speculation, and as if jokes had become the new “science”. But we can do a bit better than that!

References:

– (book) Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, 1871

– (book) Allan Keith et al., The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics, chapter 1 (by Salikoko S. Mufwene), pp.1-41.

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello and welcome to language with Chu. I hope you’ve watched the previous parts of the series. This one is just to give you a little bit more detail about Darwin and the time he was writing at. And also to share with you some of the funny theories of language evolution in case you don’t know them. So we’ll go through it quickly, but it’s just for fun.

But let’s be serious for a minute and let me remind you that Darwin wrote first “The Origin of the Species”, where he started talking about random mutations and evolution, etc. in 1861. And he kind of left a thread dangling, which is, what about man? He explained animal species and plants, but he kind of left the human being alone because he didn’t have an explanation at the time. And people like Müller (Friederich Max Müller) started making fun of him for many things, including that. But then…

So there comes 10 years later the response from Darwin, in 1871, with “The Descent of Man”. And he explains what I told you on part one of the series. But basically, for Darwin evolution of language was parallel to the evolution of mind and of man, and it was thanks to language that man was able to have more complex thoughts. And it was language and words that made a complex thought possible, because language is linear, so it allows us to organize our thoughts, etc. But you could argue that thought is MORE complex than speech then, because we can think without that linearity, we can dream without that linearity, necessarily. Never mind. At that time, that’s what they thought.

Also, given the context, this was not too strange, but now we know how ridiculous it is. When the Europeans were conquering left and right, and “meeting” with other cultures, they got to interact with their languages too. And for them, they were savage languages, and everything that wasn’t like European languages was too primitive.

For example, if a language had too complex a morphology (that means that their words were much more complex than European ones) that was because they didn’t have enough abstract thought, they didn’t know how to organize their thoughts in their heads, etc. So they needed more chunks of words, right? Except that nowadays we know the complexity of those words, and you realize how ridiculous that claim is.

If they had no morphology, like isolating languages (languages that have, like Chinese, one character per meaning or word, almost) then those people were primitive as well. They didn’t have the capacity to make beautiful French sentences or something. And it was also thought that they didn’t have any abstract terms, that all they knew how to talk about was “Me love you”, and “Me eat bison”, or whatever. That, of course, was the ignorance of the time, the imperialistic motives of the time. Now we know that that’s not correct.

But Darwin did say that language was an instinctive tendency to speak, not an instinct per se, but an instinct to learn, to learn anything. Well, okay, that still prevails today, that we have an instinct to learn. Why not? I think culture also plays a role, but obviously, we do have an instinct to learn. That’s not rocket science. But okay, let’s give him credit for that.

On the other hand came this Max Müller, and he was making fun of Darwin all the time. He said, “There’s no way you’re going to find the link between an ape, a primate, and a human being. Their difference is just too big.” I agree. He added that humans are different because they have an inner faculty for abstraction, which animals don’t have. Not so much for speech, speech comes afterwards for Müller.

But on the other hand…, they were… Supposedly they were enemies, or Müller really, really made fun of Darwin. On the other hand, he thought the same thing about the “primitive” languages. And he also thought that language had started from emotional cries that we shared with animals, and only then had rational language appeared with rationality for humans, etc. So, really, he stayed within the ideology of the times. The only thing he dared to do was criticize Darwin for jumping from primates to human beings.

BUT, thanks to Müller (and I think all of them he invented, or if not, most of them) we have some funny theories of evolution of language.

The first one is the “bow-wow” theory. And it says that speech arose from people imitating sounds that things make. So, mooo, baaahhh, etc. Very logical for when you think about the subjunctive in language, sure! Then, the “poo-poo” theory. It was automatic responses to pain, to fear, to surprise, to other emotions. So laughing became a word, gasping became a word… Don’t ask me how, but that’s how, if you follow Darwin’s logic, that’s what would have happened.

Then you have the “ding-dong” theory, according to which speech reflects some mystical resonance or harmony connected with things in the world. Well, I wouldn’t make too much fun of this one, because of what we talked about in the Sounds and Meaning series. There may be some truth to that, that speech is a reflection of something else in nature, in the universe, etc., and that we are connected to it somehow. Obviously it’s not because of that you should call a bell “dingdong” or whatever, but the idea in itself may not be so bad. That’s not Darwinian, though. Darwin was super materialistic, and so are all the academics that followed him up to this date.

Number four is the “yo-he-ho” theory, and it was rhythmic chants and grunts to coordinate physical actions when people worked together. So, I always think of the dwarves in Snow White, and how they sang together when working. “Ay-ho, ay-ho…”, etc. So, yeah, that’s supposedly how, again, a complex grammar and things like the dative case would have come about.

Number five: the “ta-ta” theory. Language came from gestures (and many linguists today still believe that it came from gestures). So, in the same way that you say “ta-ta!” to say goodbye, all languages started like that, Sure! And then finally, the “la-la” theory: when they were a little more advanced, human beings wanted to use it not just for reproduction, but they wanted language to play, to love, for poetic reasons, etc. So language evolved from singing and being poetic, etc.

I hope you see that none of these really make sense, and that from what we’ve seen up until now, it just can’t be so simple. And that we have to keep exploring and finding out where the theory doesn’t hold water, and what other possibilities there may be.

I summarized all of this up to this point by saying that I really believe that there is a design. Who the designer is (or the designers), how it came about, how it all works… I still don’t know, and I think many of you may be wondering the same. And we need to keep exploring this, because if you look at any linguistic text, you won’t find this. And if you look at many other disciplines, you won’t find it.

Archaeology, biology, psychology… there’s always a mystery. And language is one of the main mysteries of science. I’m biased, maybe, but I think it is the origin of language and who we are, and how we came to be the complex human beings that we are, why we are so different from animals, etc. And these scientists are not even looking at the complexity, from the tiniest flagellum, like Behe said, to the most complex part of language.

In language, we explored sounds before, and I barely touched on the basic principles. And you see already how complex the sound system is. That to me is almost like the equivalent of the bacterial flagellum. And as I told you before, it’s not mainstream linguistics or common knowledge, even. So let’s keep exploring, and let’s see if we find out more in the next videos.

Thanks for watching, thank you for liking the video and subscribing to my channel. See you next time!

Language Complexity – Part 4: Michael Denton on Language Evolution

In this short video, you get to hear about what Michael Denton, author of “Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis”, has to say about the problems of language evolution as it is commonly understood. Questions such as these should inspire us to let go of the dogmas and beliefs that have taken hold of the Academia for decades. How likely are random mutations applied to language? How come all humans share the same capacity in spite of living in completely different environments? Sure, you can dismiss all the arguments in this video and say that Language started earlier, and THEN spread out, but then you are only pushing the same problem to an earlier date, and you haven’t explained a thing…

References:

- (book) Michael Denton, Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis, Discovery Institute, 2016.

- (article) Joseph Warren Poushock, “Language-Wonder: Theory, Pedagogy, and Research”, 1998.

- (Book) J. C. Sandford, Genetic Entropy and the Mystery of the Genome, FMS Publications, 2015.

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello, and welcome to language with Chu. This is part four, and it’s a little bit of a bonus to recommend to you another book. It’s by Michael Denton, “Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis”. Michael Denton is one of the researchers who inspired Michael Behe. And he has a chapter specifically on language.

You know? It’s very, very hard to find texts about intelligent design, or design in general and language in the way I’m talking about right now. There is one paper that I’ll link to at the bottom, which is very good. But it’s not even famous or anything. I just found it by looking and looking. So, it’s all new, and I hope that we discover more together. But I just want to give you the basic questions to be thinking about.